Share Your Story with Trial Lawyer’s Journal

Trial Lawyer’s Journal is built on the voices of trial lawyers like you. Share your journey, insights, and experiences through articles, interviews, and our podcast, Celebrating Justice.

Stay Updated

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest from TLJ.

What Is Comparative Negligence?

Comparative negligence is a legal doctrine that addresses situations where both the plaintiff and the defendant share some fault for an accident. In personal injury cases, it determines how damages are allocated when multiple parties are to blame. People searching this term want to know how their own possible negligence (e.g., being slightly at fault for a car accident) might impact their ability to recover compensation. Key questions include: “Can I still recover damages if I was partly at fault?” and “How do courts calculate damages under comparative negligence?”

Definition of Comparative Negligence

Under comparative negligence, each party’s degree of fault for the accident is assessed, usually as a percentage, and the plaintiff’s compensation is adjusted accordingly. This means a plaintiff can still recover damages even if they were partially responsible, but the recovery is reduced by their share of fault. For example, if a plaintiff is found 25% at fault for an accident and the total damages are $100,000, their award would be reduced by 25%, resulting in $75,000 received.

Comparative negligence is a modern replacement for the older rule of contributory negligence in most places. Contributory negligence (still used in a few states) is much harsher: if the plaintiff is even 1% at fault, they recover nothing. Comparative negligence, by contrast, allows proportional recovery, which is generally seen as more equitable.

Types of Comparative Negligence Systems

Not all states handle comparative negligence in the same way. There are two main forms of comparative negligence, plus the contributory negligence rule in a minority of jurisdictions:

- Pure Comparative Negligence: Under a pure comparative fault system, an injured party can recover damages no matter how high their own percentage of fault is – even up to 99% at fault. The plaintiff’s recovery is simply reduced by their degree of fault. For instance, if you are 90% responsible for your own injury, you can still sue and collect 10% of your damages. Few states follow pure comparative negligence, but it includes large states like California, New York, and Florida. This system strictly adheres to the principle of proportional responsibility.

- Modified Comparative Negligence: The majority of states use a modified comparative negligence rule. In these systems, there is a cutoff threshold of fault beyond which the plaintiff cannot recover at all. There are two common variants:

- 50% Bar Rule: The plaintiff cannot recover if they are 50% or more at fault. In other words, you must be less than half responsible to get anything. If a jury says the plaintiff and defendant are equally at fault (50/50), the plaintiff gets $0 under this rule.

- 51% Bar Rule: The plaintiff cannot recover if they are 51% or more at fault. This rule allows recovery when fault is equally split (50/50) – in that scenario, the plaintiff could still get 50% of damages. But if the plaintiff is more to blame than the defendant (51% or higher), they get nothing. Many states have adopted this slight variation.

Modified comparative negligence aims to prevent someone who is primarily responsible for their own injury from recovering, while still allowing partial recovery if the plaintiff’s fault is minor or moderate.

- Contributory Negligence (for comparison): In a handful of states (such as Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, Virginia, and D.C.), the old contributory negligence rule persists. As noted, it bars any recovery if the plaintiff has any fault at all. These jurisdictions do not apply comparative principles – it’s an all-or-nothing approach. Because of the harsh results (even a slightly careless plaintiff gets nothing), most states abolished contributory negligence in favor of comparative systems.

It’s crucial to know which rule your state follows, as it directly affects your legal strategy and settlement expectations.

How Fault is Determined

Determining the percentages of fault is usually the job of the jury (or a judge in a bench trial). During a trial, each side will present evidence and arguments about how the accident happened and who was responsible for what:

- Evidence: Could include accident scene photos, witness testimony, expert analysis (like accident reconstruction), and police reports.

- Arguments: Each party will likely point out the other’s mistakes. For example, in a car accident case, the defense might argue the plaintiff was speeding, while the plaintiff argues the defendant ran a stop sign. Both could be true – hence shared fault.

- Jury Verdict Form: In a comparative negligence trial, the jury is often given a special verdict form to assign a percentage of fault to each party totaling 100%. For instance, they might find Plaintiff 30% at fault, Defendant 70% at fault. The judge then adjusts the damages award accordingly.

In settlement negotiations, the same concept applies informally. Insurance adjusters will assess comparative fault when evaluating claims. If they believe your actions contributed to the accident, they will reduce their settlement offers proportionally. Plaintiffs’ attorneys must counter or account for these arguments.

Effect on Settlement and Litigation Strategy

Comparative negligence can significantly impact how a case is handled:

- Settlement Considerations: If it’s clear the plaintiff has some degree of fault, both sides will factor that into settlement value. For example, a case worth $100,000 if the defendant were fully at fault might be valued at $50,000 if the plaintiff is roughly 50% at fault (in a modified state where 50% fault can still recover). Insurance companies often start by asserting a high fault percentage for the plaintiff to justify a low offer – your attorney will negotiate and present evidence to minimize your share of blame.

- Legal Strategy: Plaintiffs need to be prepared to defend their own actions. Anticipate the defendant’s accusations of your negligence and gather evidence to show you acted reasonably or that the defendant’s fault was much greater. In some cases, it might be strategic to concede a small amount of fault (if obvious) to build credibility, while vigorously disputing any greater percentage.

- Jury Persuasion: Comparative negligence arguments are about telling a persuasive story. Plaintiffs will want the jury to empathize with them and see the defendant’s conduct as the primary cause. Defendants will try to shift focus onto the plaintiff’s mistakes. How a jury perceives the parties (for example, a drunk driver defendant versus a sober but slightly speeding plaintiff) can influence how they allocate fault as much as the hard evidence.

- Multiple Defendants: If more than one defendant is involved (say, a multi-car pileup or both a driver and a vehicle manufacturer are blamed), comparative fault principles also apply among defendants. Each can be assigned a percentage of fault. Some states use joint and several liability rules in tandem, which affect how collection works if one defendant can’t pay – but that’s a complex area beyond basic comparative negligence.

Conclusion

Comparative negligence ensures that liability (and financial responsibility) in personal injury cases is distributed fairly according to each party’s share of the blame. For plaintiffs, this doctrine is generally favorable compared to older contributory negligence rules, because it means being partly at fault doesn’t automatically bar recovery. However, your percentage of fault will proportionally diminish your compensation, so the goal in any claim is to maximize the fault attributed to others and minimize your own. Understanding your state’s specific rule (pure vs. 50%/51% modified) is crucial, as it determines the threshold of recovery. Always discuss with your attorney how fault might be apportioned in your case. They can give you a realistic assessment of how comparative negligence might play out and strategize accordingly – whether it’s gathering additional evidence to reduce your perceived fault or advising you on a fair settlement in light of shared fault. In all instances, being honest about any contribution you had in an accident and addressing it head-on will put you in the best position to secure the compensation you deserve under the law.

Can I still recover damages if I was partially at fault for the accident?

Yes, in most states with comparative negligence, you can recover damages even if you were partly at fault, as long as your share of fault isn’t too high. Your compensation will be reduced by your percentage of fault. For example, 20% fault means you get 80% of your damages. Only a few states (contributory negligence states) bar recovery completely if you had any fault.

What’s the difference between comparative negligence and contributory negligence?

Comparative negligence allocates fault between parties and reduces the plaintiff’s recovery by their percentage of fault, whereas contributory negligence is an older doctrine that completely prohibits the plaintiff from recovering anything if they were even 1% at fault. Comparative negligence comes in two forms (pure and modified with 50/51% bars) allowing partial recovery, while contributory is all-or-nothing and is only used in a minority of jurisdictions today.

How do courts decide the percentage of fault in an accident?

Fault percentages are usually determined by a jury (or judge in a bench trial) after hearing all the evidence. Each side presents evidence of the other’s negligence, and the jury assigns a percentage of blame to each party totaling 100%. This can involve reviewing accident reports, expert testimony, and witness accounts. In negotiations, insurance adjusters make their own fault assessments to guide settlement offers. If a case goes to trial, jurors might, for example, decide a plaintiff was 30% at fault and the defendant 70% – the court would then reduce the plaintiff’s damages by that 30%.

Which states follow contributory negligence versus comparative negligence?

Only a few still follow contributory negligence: Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, Virginia, and Washington D.C. are notable examples. The vast majority of states use some form of comparative negligence. Approximately one-third of states (including California, New York, Florida) use pure comparative negligence, allowing recovery even if the plaintiff is very mostly at fault. The rest use modified comparative negligence with a 50% or 51% cutoff (for example, Texas and Georgia use 51% bar, while Tennessee and Arkansas use 50% bar). It’s important to check your own state’s law to know the rule that will apply to your case.

Featured Articles

-

Glossary

What is a Demurrer Judgment?

What is a Demurrer Judgment? A Demurrer Judgment is a court ruling issued after a defendant files a demurrer, arguing that the plaintiff’s complaint.

-

Glossary

What is the TPPRA?

What is the TPPRA? The TPPRA, or Third Party Payor Recovery Act, is a legal statute—most notably used in states like Texas—that gives third-party.

-

Glossary

What are Jury Instructions?

What are Jury Instructions? Jury instructions are the formal legal directions given by a judge to the jury before deliberation in a trial. These.

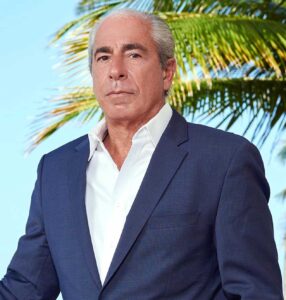

Explore our Contributors

Discover Next

Insights from Experts

Learn from industry experts about key cases, the business of law, and more insights that shape the future of trial law.